For America’s friends in Asia, the uncertainty brought by the impending return of Donald Trump to the White House is coming at a bad time.

China has been modernizing its military and nuclear arsenal while becoming increasingly aggressive in asserting territorial claims in the South China Sea and over Taiwan. North Korea has ramped up its belligerent rhetoric and calls to develop its illegal nuclear program. Both countries have expanded their alignment with Russia as it wages war on Ukraine, linking Asia to the shattered peace in Europe.

For decades, the US has backed the security of its allies in the region, which has more overseas active-duty American troops than anywhere else in the world. Tens of thousands of soldiers are stationed on sprawling bases in treaty allies South Korea and Japan, countries that, like the Philippines and Australia, the US is bound to aid if they come under attack.

Those countries are now preparing for the return of an American leader who has railed against what he sees as free-riding US allies who don’t pay enough for defense, sidled up to autocrats, and called for an “America first” approach to global obligations.

Many questions about Trump are on the minds of US-aligned leaders in Asia, observers across the region say.

Will Trump ask for more defense spending than allies can afford? Could he take an extreme step to withdraw US forces if any such demands aren’t met? Will the businessman-turned-leader cut deals with Chinese leader Xi Jinping, North Korea’s Kim Jong Un or Russia’s Vladimir Putin that undermine the interests of US allies?

Alternatively, could he perhaps strengthen US alliances and be a tougher opponent for America’s enemies?

In the shadow of this uncertainty, leaders across the region have been scrambling to forge strong ties with the notoriously mercurial incoming US commander-in-chief, who’s known to link foreign policy to personal rapport.

Many are warily eyeing President-elect Trump’s threat to ringfence the world’s largest economy with 10% tariffs on all imports and upwards of 60% tariffs on goods from China, moves that could have significant economic knock-on effects across Asia.

But as Trump’s January inauguration draws closer, governments across Asia are also facing potentially more existential questions about how Trump will manage US security relationships with friends and rivals – and stand by its allies if tested.

‘Indispensable power?’

After World War II, a network of US alliances was established across the world to serve as a powerful deterrent against another global war. A major aim was to prevent more countries from becoming nuclear powers by placing them under the umbrella of the US arsenal.

In the eyes of many in Washington and across Asia, those alliances in Asia-Pacific have only become more critical as relationships in the region become more contentious.

China has expanded its security ties with NATO-adversary Russia and been accused of enabling Moscow’s war by buying up Russian exports and providing the dual-use goods needed for its defense base. Beijing has also ramped up its intimidation of Taiwan, the self-ruling democracy it claims and has vowed to take control of, by force if necessary.

In the South China Sea, the China Coast Guard has in recent months attacked Philippine ships with water cannons and even axes, despite a major international ruling years ago denying its claim to the bulk of the strategically critical waterway.

North Korea, meanwhile, has ramped up its threats toward South Korea and the US as it carries out illegal weapons testing. It’s also aiding Russia’s war with ammunition, missiles, and – in a major, recent escalation – soldiers, US officials say.

But as Trump steps onto a more fraught and complex global stage than at the start of his first term eight years ago, observers in Asia say his focus appears to be on ratcheting up economic pressure on China rather than regional security.

Trump’s “priority is overwhelmingly on the economic relationship and on the United States not losing to China economically,” but there’s little sign “that he is deeply interested in the military or strategic balance in East Asia,” said Sam Roggeveen, director of the Lowy Institute’s International Security Program in Sydney.

“Everything points in the opposite direction,” Roggeveen said. “He’s interested in – sure – having a strong military and defending the United States … but not in this idea of America as an indispensable power which has a unique global security role.”

The incoming leader and his strategists have instead repeatedly questioned whether the US was getting enough out of its alliances and whether American lives should be lost and dollars spent fighting foreign wars.

Trump shocked European leaders earlier this year by saying he would encourage Russia to do “whatever the hell they want” to any NATO member country that doesn’t meet the US-led alliance’s defense spending guidelines.

Preparing for Trump 2.0

Weeks before election day, Trump turned that spotlight toward Asia, claiming during an interview with Bloomberg News that were he president, South Korea would pay $10 billion a year to host US troops — about eight times more than Seoul and Washington recently agreed on.

South Korea already spends well over 2% of its gross domestic product on defense, considered by the US to be a benchmark for its allies. Over the past decade, the country has also paid 90% of the cost for expanding Camp Humphreys, the US’ largest overseas base.

But Trump’s comments have sparked fears in Seoul that he could seek to renegotiate cost-sharing for US troops, despite a five-year agreement reached earlier this year that will raise Seoul’s spending to 8.3% more in 2026 than the previous year. A failed renegotiation – in a worst case posed by some observers – could result in a Trump decision to downsize or withdraw US forces meant to counter the threat from its belligerent northern neighbor.

Such a scenario, or broader feelings that US commitment is waning, could also push Seoul toward developing its own nuclear arsenal – a potential first step on a slippery slope that could lead more middle powers to proliferate such weapons, experts say.

But dealings with Trump have become a lot more complicated for South Korea. Lawmakers there voted to impeach President Yoon Suk Yeol earlier this month after his shock declaration of martial law, and then weeks later voted to impeach acting president Han Duck-soo. The country now faces months of political uncertainty at a time when observers have said building a strong leader-to-leader relationship is key.

“The biggest challenge is whether Seoul and Washington will be able to communicate properly,” said Duyeon Kim, a Seoul-based adjunct senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security.

Such communication is key to “avert devastating consequences and surprises in the US-South Korea alliance that we currently assume would happen based on Trump’s harsh rhetoric against allies,” she added.

In Japan, pundits have lamented the perceived deficiencies of Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba compared with the late Shinzo Abe, known as Asia’s “Trump whisperer” for his finesse in getting close to the president-elect during his first term.

The key American ally in Asia is likely to stress its own sweeping changes to its defense posture since Trump was last in power.

Tokyo has veered away from the pacifist constitution imposed by the US in the aftermath of World War II, in 2022 moving to boost defense spending to about 2% of its GDP by 2027 and buy up American cruise missiles.

Countries throughout the region are also watching whether the Trump administration picks up the mantle of a key piece of Biden’s legacy: efforts to build across Asia what State Department officials have called a “lattice work” of interwoven US partnerships, part of the administration’s “invest, align, compete” strategy to counter Beijing.

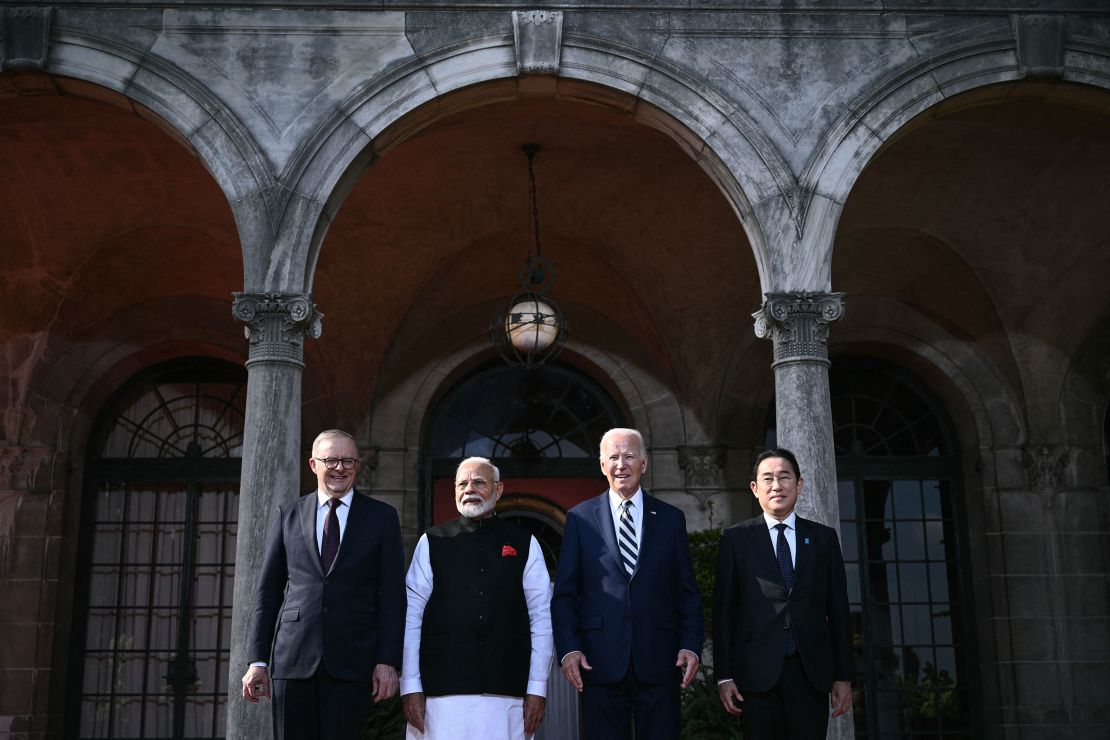

Biden bolstered the Quad (India, Japan, Australia and the US) security group and founded the AUKUS (Australia, United Kingdom and the US) partnership that aims to equip Canberra with nuclear-powered submarines. He also brokered significant increases in Japan’s security coordination with South Korea, the Philippines and Australia.

Trump – as an unpredictable force in the White House – could drop, maintain or even deepen these relationships. But in the meantime, America’s Asian allies will look to hedge against any decline in US support.

“The United States is now not the constant of international affairs, but rather the variable,” said Murata Koji, a professor of political science at Japan’s Doshisha University.

“That’s why we have to expand our security (outside) the United States,” he said, pointing also to Tokyo’s need to deepen its partnership with Europe over shared concerns.

China watching closely

That said, experts across the region broadly feel it’s unlikely there will be seismic changes in the US security presence under Trump, in terms of drawing down troops or tearing up alliance agreements, especially given American focus on the challenge posed by China.

“Geopolitical realities and circumstances will oblige him to try to maintain forces in the region. The scenario that I’m thinking of is more of renegotiating, more than outright withdrawal,” said Collin Koh, a senior fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore.

And countries will not just be considering potential downsides to Trump’s return, Koh added, pointing to perceptions in Asia that Biden has hesitated in some of his decisions on Ukraine, complicating the situation for the besieged country.

“With Trump coming in, there could be some renewed hope that (he) will not be like Biden in terms of crisis – maybe Trump will be more decisive,” he said.

There are concerns, however, that an expected aggressive economic policy toward China could lead to a further breakdown in communication between the US and Chinese militaries, raising the risk of confrontation between the two. And if US allies are hurt by new American tariffs, they may have no choice but to rely more on the world’s second-largest economy.

On the other hand, Trump also signaled some interest in working with China, implying in recent comments to CNBC that he saw at least certain aspects of his post-pandemic policy on China as “a step too far.”

Then there is the question of how Trump deals with Taiwan – a potential flashpoint long seen as among the most likely triggers for a US-China conflict.

An ‘insurance company’

Biden repeatedly broke with purposeful American ambiguity to say that the US would defend Taiwan if China invaded the island. He also approved funding for the first-ever military aid to the island as Beijing ramped up its military pressure.

In contrast, the president-elect earlier this year appeared to undercut US relations with Taipei, claiming in a Bloomberg interview that Washington was “no different than an insurance company” for the island and said Taiwan should pay the US for defense. In October, he told the Wall Street Journal he would impose 150% to 200% tariffs if China went “into Taiwan.”

But how the Trump administration would react in the event of a contingency remains unknown. Trump’s choice for secretary of state, Sen. Marco Rubio, is a staunch advocate for the island, and his vice presidential pick JD Vance has argued that the US supplying Ukraine with air defense systems could hurt its ability to aid Taiwan’s defense if China were to attack.

That argument, however, has observers in Asia concerned.

Many in the region believe how Trump handles the war in Ukraine will send a critical message to Russia’s partners like China, Iran and North Korea – a set of nations some in Washington fear could harden into a dangerous axis. Those concerns may be particularly acute when it comes to China, which has likely been watching closely as it looks to its own intentions in Taiwan.

Trump has suggested he would end the Ukraine war “in 24 hours” and called for an “immediate ceasefire and negotiations” – a position that jives with Beijing’s stated stance on the war, which the US and its allies have criticized as being beneficial to Russia.

“I know Vladimir well. This is his time to act. China can help. The World is waiting!” Trump said in a post on his social media platform Truth Social earlier this month.

And what that rhetoric means in practice could have significant ramifications for Asia.

“If Russia is allowed to walk away with looking like it’s got a win from this … that then cements this relationship (between Russia and China),” said Robert Ward, director of geo-economics and strategy at the International Institute for Strategic Studies in the UK.

“And Xi Jinping will be watching this very closely, watching – how credible is Western deterrence? How credible is NATO? How willing is the West to actually put skin in the game in a conflict – and that of course relates back to Taiwan.”